In working on Hundred Dungeons, there’s an area in which I’ve noted the most confusion and mismatched expectation from players and other GMs: the flow of the game, or “gameplay loop” as they like to call it in the video game world.

Certainly a goal of mine in designing this reimagining of D&D 5E has been to bring back an old-school mindset for how a campaign is put together, specifically emphasizing the player-driven expedition as the fundamental activity of the game. Those who have played in OSR and especially west marches style games are familiar with how such play defies the model of the linear adventure that strongly “suggests” the “correct” path for players to pursue.

Where many groups, GMs, and published scenarios depart from this model is in their desire to choreograph the sequence of events. It’s a funny balancing act that linear design forces us to do: to meticulously curate incentives so that players find out where they’re supposed to go without being explicitly told. And I guess we don’t want to tell them because we’d be revealing the secret behind the magic trick: that in the end their agency was limited to the encounter level. They never had a say in where to go and when.

Personally, that rarely works for me. As a player I get bored. As a GM, I tend to break apart the predetermined sequence and rearrange the pieces into a meaningful choice of some kind.

I suspect this has something to do with the rise of the “boss fight” as the quintessential endgame in fantasy RPG adventures. Obviously, a combat with a dungeon boss existed very early in the game (at least as early as 1976’s tournament module The Lost Caverns of Tsojconth, the one spelled with an ‘o’), but somewhere between then and the present, we started insisting these encounters come last, even if that meant funneling players into all the other content first.

In 2020, I ran The Sunless Citadel for a group who lit the blight groves on fire and ran away before confronting Belak at all. I was taken aback, but quickly felt a thrill that they had been empowered enough to stop worrying about whether I expected this or thought it was correct. Their final escape was still exciting: the blights and enemies poured out from every area to pursue them. That experience taught me to relax and give up enforcing a sense of sequence.

What I find most rewarding about putting players in charge of their own goals and the sequence of their expedition is that I can focus my energy on being interested in and responsive to the players’ choices. I don’t have to worry about exerting influence. I can instead focus on providing points of engagement, and if the players aren’t interested, I let them move on and show me what they are interested in. Because they decide where to go and how far, the dungeon crawl (or whatever it may be) better embodies the push-your-luck game it should be.

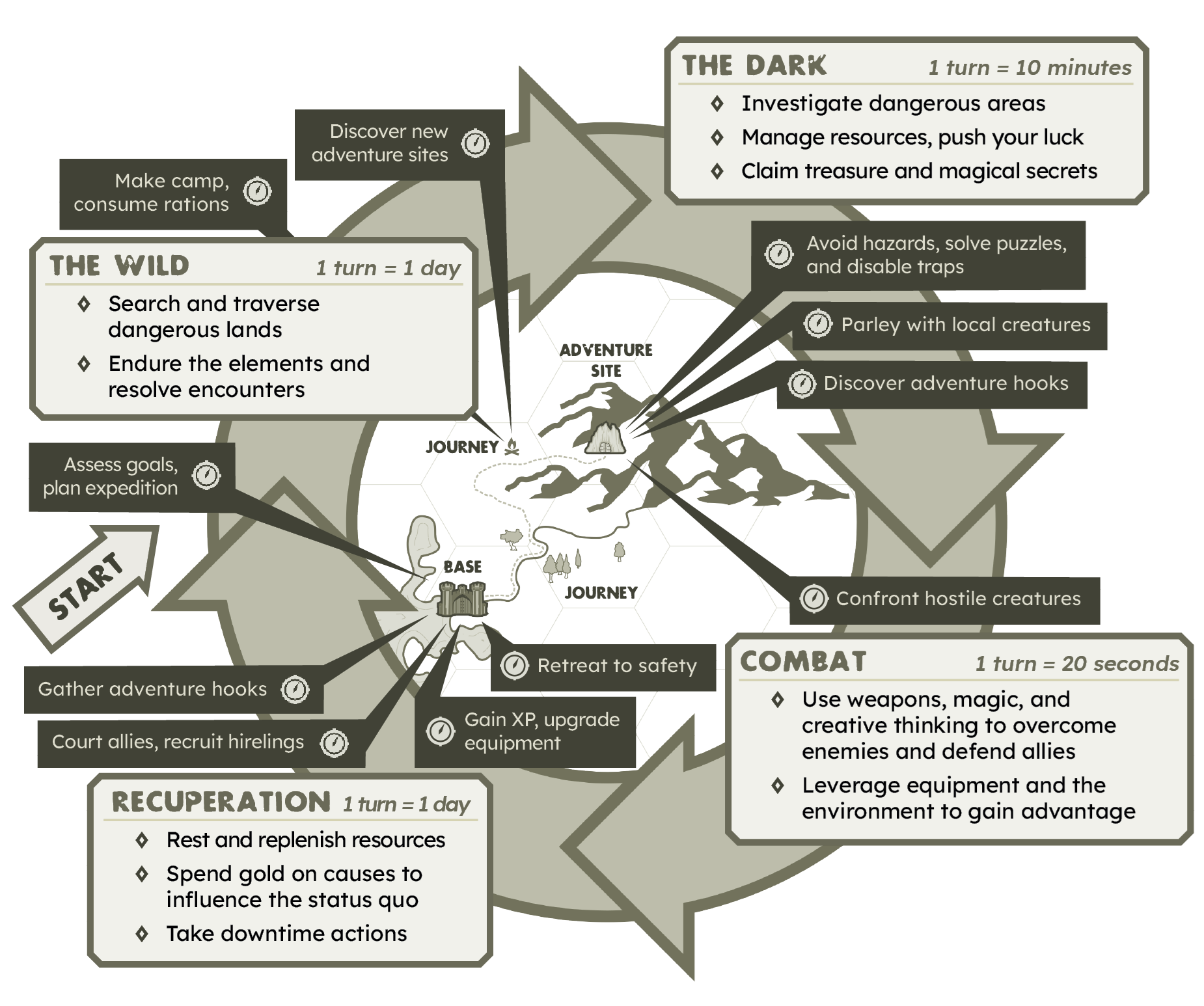

So all of that is a long prologue to this excerpt from the upcoming Game Moderator’s Guide for Hundred Dungeons. In an effort to teach the open world model of campaign, I put together a “gameplay cycle” that integrates adventuring activities into a loop emphasizing player agency and reinforcing the cyclical expedition as the fundamental structure of the game. Enjoy!

GAMEPLAY CYCLE

As the GM, your role is to ensure the game cycles smoothly from phase to phase while engaging and rewarding players. The diagram above maps how this gameplay cycle fits the adventure phases together into a looping pattern of discovery, risk, and rewards. Following the guidance in this section can make the difference between an engaging sandbox and an aimless slog.

In your game, characters venture forth from safety into dangerous locations, where they push their luck, make the most of their resources, and face mortal peril. Once they’ve extended themselves as far as they can, the heroes return to safety to rest, upgrade, and gather information for another expedition.

To avoid overhwelming players with complete freedom, you’ll provide various engagement points each step of the way, like handholds on a climbing wall. If you consistently keep one or more of these engagement points within reach of the players, they’ll always have a next step.

The essential framework of the game world consists of a Base, the Adventure Site, and the Journey between them. In all the following acitivity, players decide on their own goals, where they go to achieve them, and how long they stay before returning to safety. Your job as the GM is to provide information and engagement, not to predetermine the “correct” path.

Starting at Base

Here there is relative safety and stability. Whether the campaign map is dotted with settlements, or its only secure place is a wandering merchant caravan, these Bases provide an environment to which players can return for Recuperation.

At the start of the game, the players assess their goals and plan an expedition outside the safety of Base. To ensure players have enough information to choose goals and make a plan, use a campaign brief (described on page 5).

Journey

The space between Base and the Adventure Site is a source of danger, discovery, and unexpected encounters. While traversing it, players enter the Wild phase, where they often make camp between days of travel, and consume rations to avoid exhaustion.

Journeys are connective tissue, so what happens in that space should draw the characters toward locations on the campaign map. As they discover new Adventure Sites, the game world expands, opening avenues for continued play.

Some encounters in the Wild become their own opportunities for adventure, such as an Adventure Site discovery or unexpected battle. The cycle can then move quickly into the Dark or Combat as necessary.

Adventure Site

These places can take any form imaginable — an abandoned mine, a tower, a dark alley, or even a reality-bending plane of existence — as long as there are risks, secrets, and treasure to be found. At the Adventure Site, PCs move to the phase called the Dark.

How far the characters delve depends on how they manage resources like equipment and spells. The further they go, the more treasure, magic, and knowledge they recover from the Site.

Common challenges at an Adventure Site include avoiding hazards, solving puzzles, and disabling traps. Characters may need to parley with local creatures or factions within the Adventure Site, while discovering adventure hooks that deepen their understanding of the world and serve as a springboard for future expeditions.

Should denizens of the Adventure Site (human, monstrous, or otherwise) become violent, players enter Combat and will need to confront the hostile creatures. This sort of deadly conflict quickly drains resources and hastens the end of the expedition, one way or another.

Adventurers may engage in many Combat phases before they retreat to safety at their Base, but the time always comes when their resources no longer support further exploration of the Adventure Site. Choosing the moment to retreat is a crucial part of the players pushing their luck in hopes of rich reward.

Returning to Base

Once back at Base, characters enter Recuperation, a time to rest, replenish their resources, spend the gold they’ve claimed, and take downtime actions.

In addition to gaining XP and upgrading equipment, Recuperation is about deepening the characters’ relationship to the world by courting allies and recruiting hirelings to help in future expeditions. NPC contacts created during downtime actions should persist from cycle to cycle and express their goals and perspectives. This encourages players to also form goals and points of view on the events of the wider world.

As before, the Base is a place to gather adventure hooks, assess goals, and plan an expedition. From there, the gameplay cycle repeats for as long as you and your players wish to continue the game.

What do you think of this depiction of the gameplay loop in an old-school game?